Nunc Dimittis

Towards the end of 2017, as medical specialists explained to me that no further treatment was possible and that, therefore, my bowel cancer would probably be terminal, I started to seriously reflect on my life. And I realised that it has been rather compartmentalised, a series of chapters, some bearing little or no relation to others.

Few of my current circle of friends, for instance, are familiar with my background, my family, my various careers or those people who have influenced me over the decades. Likewise, I would not expect friends, colleagues or acquaintances from years ago to know what has happened in the intervening years. So I set about writing this illustrated reflection of my 60+ years.

I sincerely hope that recipients of the music award that I expect to have been established posthumously at the Royal College of Music in the name of Ged Clapson and Blair Wilson will search out this online resource and discover a little more about me and the man who brought such happiness and love into my life; and it will help them to understand my motivation for supporting their studies at the RCM. And, should anyone choose to say or write a few words about me following my death, I hope this might provide them with a reasonably complete picture.

I am not pretending it is complete: others may have completely different recollections. It is also inevitably selective: there are episodes which I have either deliberately forgotten or the memory has chosen to suppress. I will not even pretend it is totally accurate: it is my interpretation of events and the mind has the habit of playing tricks in our later years.

If you lived through any of these events with me, feel free to add any blank scenes or perspectives. And if you are visiting as a stranger, welcome! Here, for what it's worth, is my personal account of my life ...

I

The child who is born on the Sabbath day

Is bonnie and blithe and good and gay.

20 March 1955 was a Sunday: Mothering Sunday. It was also the day that Charles (named after my father) Gerard Clapson made his first appearance in the world. Apparently, my mother – a staunch Catholic – had no idea when they chose my middle name that St Gerard Majella was the patron saint of expectant mothers. But it was the one I came to be identified by, to differentiate between my father and me. Besides, I always tried to avoid the name Charles (it sounded so snooty when I was growing up), but in my later years, I have resigned myself to the fact that my birth certificate clearly states that I am Charles Gerard.

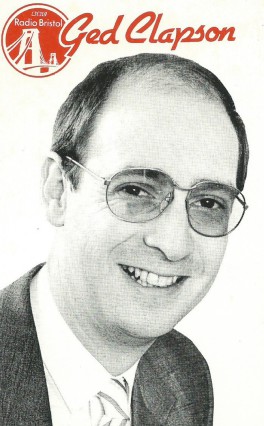

From an early age though – before I was one year old – I started being called Ged or Geddy. For a short time in the mid-1970s, I was known as Gerry; but when I began broadcasting with BBC Radio in Bristol, I was asked whether I had an alternative, since they already had one Gerry (Parker). Ged seemed a natural choice.

I came on stage in 1955 at 28 Ravenswood Road in Redland (below), a suburb of Bristol, adjacent to Clifton. The fourth of five children, I was the first and only son of Charles and Kathleen (née Harrison); indeed, I was (and still am) the only remaining male Clapson in this branch of the family. So, although there might be distant relatives in some far-flung corners of the world, and since I have no children, the family name will die out with me.

Home was a semi-detached house (probably built in the Edwardian period), set over three storeys with a large sloping L-shaped garden to the rear. Foremost among my memories of Number 28 is that it was cold: physically and emotionally. These were the days before central heating; occasional two-bar electric or New World gas fires were turned on only when needed, and the gas cooker provided welcome warmth in the kitchen. I well remember waking up in the morning to find a sheet of ice on the inside of my bedroom window.

The emotional environment was often bitter too. It is hard to recall the warmth created by love or laughter. It was tense, rather than aggressive; impatient, rather than affirming; critical, rather than embracing. Rows and traumas were regular occurrences, and I reacted as many children do in such circumstances, with nocturnal bed-wetting, that went on well into my teens (and, occasionally, beyond). When voices were raised downstairs, I was invariably sent to my room, so I rarely knew what the arguments were about. Infact, it wasn't until I was in my 40s or even 50s before I discovered what some of these family issues were that caused such dissent; and - to be honest - there may well be further skeletons in the closet which have still to be revealed. But that is purely conjecture. It was a life peppered with 'secrets' too ... and we were remarkably good to keep them when told something in confidence! The problem was: we often kept them too well, so, many years down the line, it has not been uncommon to have a conversation that hinged on 'But didn't you know?!' The simple answer was 'No, I never knew, because you told whoever in confidence and they respected your wishes!'

These days, such an environment would be classified as abusive – emotionally, if not physically (although there were certainly occasions of corporal punishment). But, on reflection, it was probably the result of the age into which I - and my siblings - were born. Whether children of the Second World War or born shortly after it, these were bleak times. Resources were rationed - and so were emotions. Britain in the middle of the 20th century still carried the baggage of Victorian morality and the bitter memories of two World Wars and all the austerity that came with them. My parents had married in March 1939 and my father, being in engineering, was in a Reserved Occupation, which meant he was spared conscription. I knew little about my parents' upbringing; and I can't recall a single moment when either of them spoke lovingly about a happy childhood. Maybe it was inevitable that their children were destined to inherit the same. Whatever the reason and our personal scenarios, each of us, in our own ways, simply learnt to accept – and expect – it. Gradually, the family unit shrunk, as first one, then a second sister left home - both under a cloud of silence and, for me, of ignorance as to the reasons for their departure.

Born just days before the start of World War II, Jacky was (and still is) my eldest sister and, being 16 years older than me, I probably saw her as my proxy mother until she left to start her own life away from the tense atmosphere of the family home. I always considered her to be the more studious of my three sisters, the one destined for university after La Retraite High School for girls, where they were all pupils. Sue also left home, under mysterious circumstances (at least for me, as a young boy), and it wasn't until after her death at the age of 66 in 2013 that I came to know her son, Mike, whose birth was a family scandal that precipitated his mother's departure. Between these two was Anne, who remained a steadying influence in my young life, until long after the arrival of a baby sister in 1960. Now known as Lucy (the third of her forenames), she was five years my junior and acquired 'Boo' as a family nickname.

Home life was dominated by my mother (a native Yorkshire-woman). Looking back now, it is obvious that an early marriage (a month before her 19th birthday) and motherhood had left her frustrated and with unfulfilled ambitions. But, as her children grew older and more independent, she was determined to rectify that, first by studying for and achieving two O-levels (English Literature and Human Biology) and then by working at the Medical Illustration Department at the Bristol Royal Infirmary.

It always felt as though mother wore the trousers at home, and my father (a Londoner) was in a subservient role, summonsed only when major family decisions needed to be made or discipline needed to be imposed - or so it seemed to young Ged. The children - including myself - were expected to help with the domestic chores. So, throughout my childhood, play and studies were always supplemented by a diet of assisting with the cleaning or gardening, ironing or, occasionally, cooking, and even the odd bit of sewing! All in all, by the time I left home in the autumn of 1973, I was equipped with domestic skills that would prove invaluable in later life.

My parents had moved to Bristol from Sutton in Surrey after the Second World War, in the hope that the West Country air would be kind to my mother's asthma. In time, they bought the house in Ravenswood Road; and it was from here that I set off for the walk to primary school in Clifton (probably more than a mile and a half) in September 1960 (above).

II

“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts …”

Jaques in As You Like It (William Shakespeare)

The Pro-Cathedral School sat in the shadow of the Pro-Cathedral itself, both institutions perched precariously on a cliff-side on Park Place. The church opened as a place of worship in the mid-19th century and served as the mother church for the Catholic population of the Diocese of Clifton until a fully consecrated Cathedral could be completed: that wasn’t to be for more than 120 years, when the Cathedral Church of SS Peter and Paul was opened. In the meantime, the Pro-Cathedral Church of the Holy Apostles sufficed, with its adjacent primary school providing an education for youngsters such as me and facing a triangular garden that was rich with cherry blossom each May that coincided wonderfully with First Holy Communions.

The picture above shows the Pro-Cathedral Church in the foreground, with the ruined presbytery to its rear. The junior school playground ran the entire length of the nave. Visible over the houses is the 'new' Cathedral of SS Peter and Paul.

With two infants’ classes and four for the juniors, the primary school’s staff seemed to be predominantly middle-aged spinsters, supplemented by the headmaster's wife, Doreen Vassalli, and two teaching sisters from nearby St Mary’s Hospital – Sister Maria Carmel who taught Junior 4, and Sister Maria Gertrude who taught the younger children. Both were members of the Poor Servants of the Mother of God (PSMG), and I had a particular affection for Sr Gertrude, a kind and gentle nun with whom I kept in touch for many years after leaving ‘the Pro’. Sr Carmel, on the other hand, had a reputation for being more tyrannical and I always resented the way she insisted on addressing me as Charles, because there was another (older) Gerard in the class.

The ritual of getting to and from primary school back in the 1960s involved my elder sister, Anne, and our maternal grandmother, known as Nana. Since Anne was working in an administrative role at Midland Assurance on nearby Queen’s Road at that time, she would take me to school in the morning and walk me home in the evening. But there was a time lapse between the end of the school day and the end of her working day in the office; so that time was spent around the corner at Nana’s, a basement flat in Meridian Place, where the daily ritual included an episode of the 1960s ITV soap opera ‘Crossroads’.

The Pro provided me with a solid Catholic education and even gave me my first opportunity to tread the boards, on the school stage that was sited beneath the church: I danced a Scottish jig to Andy Stewart’s Donald, Where’s Your Troosers? The theatrical seed had obviously been sown, because I then went on to perform occasional plays for relatives and friends with my younger sister, Lucy, and the Kissane sisters from another parish family. One of the most memorable was our version of All Gas and Gaiters, a television sitcom of the late 1960s, in which I played the bishop!

This period also gave me my introduction to several different genres of music which, in one way or another, have remained with me throughout my life. With little or no interest in the ‘pop’ culture of my contemporaries, I found myself uplifted by my father’s Classical LPs, especially Rimsky-Korsavok’s Scheherazade and the Readers Digest collection of piano works performed by Artur Rubenstein. But no composition affected me more powerfully than the sensual strings and bombastic brass of Tchaikovsky's 6th Symphony (The Pathétique): this gay Russian composer's passion and pain - as represented in his glorious music - seared itself on my musical DNA.

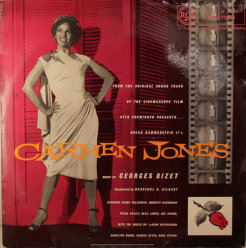

But there was another vinyl collection at Ravenswood Road as well, that made an impression upon me: the musical. From Oliver! to The Sound of Music, West Side Story to Guys and Dolls, I was captivated by Anne's selection of discs and the ability of composers and lyricists to tell stories and explore emotions through their music. And nowhere more so than in Carmen Jones (above), which (unbeknown to me at the time) has going to play such a significant part in my later life and which gave me my first taste of opera.

The Pro-Cathedral (church) provided me with a community in which I immersed myself – not least as an altar-server from the age of seven. The dusty, musty building was full of shadows and mystique, with ethereal light shining through stained glass windows, the smell of candle wax and incense, the sound of the majestic organ, choristers and a massive ticking clock at the back of the church which I volunteered to wind regularly.

The rituals were theatrical and rich with characters and symbolism; and I became absorbed by the splendour of the Catholic faith immediately before, during and after the Second Vatican Council. Sometimes it felt like I was spending more time in church than at home: serving at the early morning weekday Masses, as well as on Sundays; taking part in the Holy Week and Easter liturgies, not only at the Pro itself but also at La Retraite Convent and St Joseph’s Home for the Elderly; assisting at baptisms, funerals and weddings (including Anne's to her husband, Terry); and even traipsing over the Clifton Suspension Bridge to Leigh Woods at the crack of dawn to serve at Mass for Bishop Joseph Rudderham, which concluded each morning with a fine cooked breakfast served in the kitchen that was dominated by the cast iron range cooker: Bishop Rudderham's house-keeper, Sister Anastasia, certainly knew how to pamper hungry altar boys!

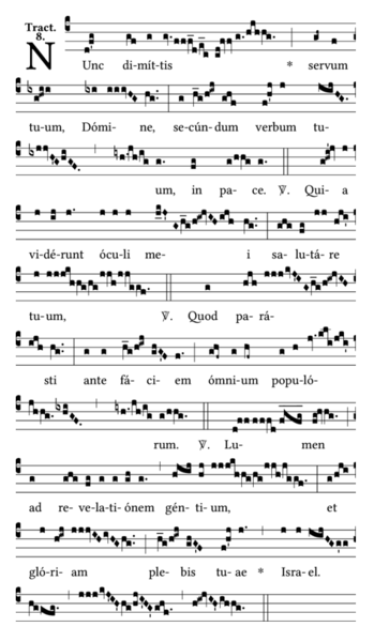

Socially, as well, there were annual camping trips from the Pro-Cathedral to Buckfast Abbey in Devon, led by Father Martin Fitzpatrick. Having pitched our tents in the orchard, we experienced the freedom of the Exmoor countryside, with its rivers and lakes, its woods and its moors - as well as the culture of monastic life in the Abbey itself. A highlight of these summer excursions for me was undoubtedly Compline - the last service of the day - played out in semi-darkness (above), and especially the soulful incantation in Gregorian Chant by the Benedictine monks of the 'Memorare' and the ‘Nunc Dimittis’.

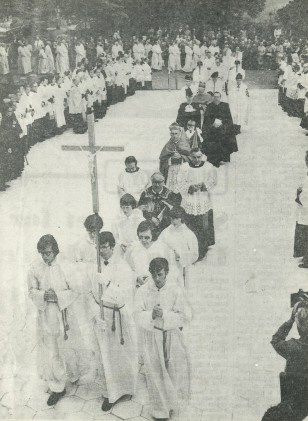

When the doors of the Pro-Cathedral finally closed at Park Place and the splendid (though architecturally very different) Cathedral of SS Peter and Paul was consecrated on 29 June 1973, there was I, leading in the procession as acolyte - pictured here to the right of the cross-bearer. Among the dignatories following us are the Apostolic Delegate to Great Britain; Cardinal John Carmel Heenan, who preached at the ceremony; and Bishop Joseph Rudderham of Clifton, who presided at the consecration.

All things considered, then, it is little wonder that, from the age of seven, I had only one ambition: to join the ranks of the priesthood, an ambition that remained strong as I entered puberty and moved from the Pro-Cathedral primary school to St Brendan’s College in Brislington.

III

“People come—they stay for a while, they flourish, they build—and they go. It is their way. But we remain. There were badgers here, I’ve been told, long before that same city ever came to be. And now there are badgers here again. We are an enduring lot, and we may move out for a time, but we wait, and are patient, and back we come. And so it will ever be.”

Mr Badger, Wind in the Willows (Kenneth Grahame)

St Brendan’s College (right) was the domain of the (Irish) Christian Brothers, an almost totally male environment, and the ethos was a combination of academic industry (with all eyes on university) and sporting prowess. Unfortunately, I shone in neither area. I was not one of the brainiest boys in class; neither did rugby or cricket appeal to me. But I attempted Latin (because I thought I might need it as a Catholic priest) and even Ancient Greek, though I failed both subjects dismally at O-level. I coped adequately but not spectacularly with the other core subjects, especially English Literature, which I later took to A-level (and passed) in 6th form. I chose athletics instead of cricket at the first opportunity and even made the school team, briefly, in the high jump; and I opted out of rugby to run miles across muddy fields and windswept lanes in cross-country. I even found myself actually enjoying being a member of the Air Force branch of the Combined Cadet Force, an activity that gave me my first experience of flying – in a Chipmunk – at an RAF camp in East Anglia.

But sports and studies aside, St Brendan’s was significant because it introduced me to the theatre-proper. Our English teacher, Peter Allen, organised regular excursions to plays at the Bristol Old Vic and it was often left to me to review the productions for the school magazine. And when the opportunity arose to audition for the school’s production of ‘Toad of Toad Hall’, there was no holding me back. Under the watchful eye of drama teacher Hedley Goodall and his assistant, Alan Lawrence, I had already been enraptured by the previous year’s ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’; and I was determined to get involved in A.A. Milne’s adaptation of Kenneth Grahame’s classic, ‘The Wind in the Willows’. Enter Mr Badger – centre-stage beneath a pile of leaves – awakened from his slumbers by an energetic Mole who sat down on him! The make-up; the costumes; the lights; the script; the scenery … I was transported to another world in which people paid to watch me perform, clapped and cheered, and made me feel like a success. I could be an animal, a character, a grumpy old badger, and all at the tender age of 15. I loved it! Ged the Thespian had arrived!

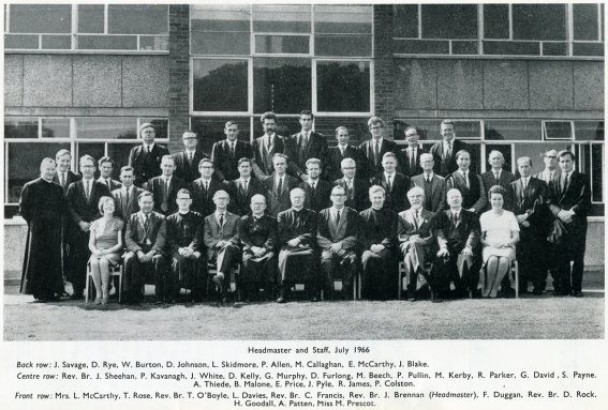

Pictured below are the staff of St Brendan's College in 1966. They include three of my form masters during my time there - Peter Allen, Tony Patten and Dan Kelly - as well as John Savage (woodwork), 'Chalky' White (chemistry), Maurice Kerby (geography), Lionel Davies (art), Peter Pullen (music) and Elwyn Price (sport - especially rugby!). Also in the front row is Hedley Goodall who had such an influence on me as a performer.

I realised in later years that I never had the looks to play the handsome romantic lead – or the tenor voice for it in musicals; but the older, character roles were far more interesting. And it wasn’t until much later – in 2014, in fact, at the age of 59 – that I was to finally play a role which was appropriate for my real age: Thomas Oakley in ‘Goodnight Mr Tom’.

One Saturday in the summer of 1971, my parents informed that the latest increase in fees at St Brendan’s College was beyond their means, so I would be re-enrolling at St Bernadette School (above) from the autumn term. Having spent the first five years of my secondary education at a direct grant all-boys grammar school, the move to a Catholic comprehensive in Whitchurch for the 6th form was something of a culture shock. Besides, I didn’t have the chance to bid farewell to my friends in Brislington. But the educational environment for A-level studies was pleasant enough, even if it seemed strange to be studying alongside girls again.

Inevitably, throughout these teenage years, I had been developing sexually; although, to be honest, since my mind was still firmly fixed on the priesthood and the consequent demand of celibacy, it didn’t feel like more than an interesting distraction most of the time. Indeed, my planned vocation provided the perfect excuse for fending off any female attention. It was about this time that I started to attend the First Friday Masses in the crypt of St Mary-on-the-Quay (pictured here) – the neighbouring parish to the (Pro) Cathedral that was administered by the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). Mass was followed by a disco and my intention to study to be a Catholic priest was the ideal defence to deal with the amorous advances of Margaret O’Neill, who insisted on singling me out for the slow final dance!

At St Bernadette School, however, it was my male peers whom I found sexually attractive – especially Paul Gill. Looking back on it now, it was immature and offensive, but at the time, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world to bombard him with anonymous romantic poetry. As far as I know, he never suspected the source; and, at the time, there felt nothing wrong with it: I was simply expressing my affection and admiration for another human being. Poor Paul!

I successfully got two A-levels at St Bernadette’s, in English and Geography, which was a bit of a surprise since I expected to get French as well (and probably fail Geography). But romance and studies aside, my two years at the Whitchurch school were memorable in other ways as well. Continuing my interest in theatre, I landed the role of Major-General Stanley in Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘The Pirates of Penzance’. This was another new experience: not only musical theatre, but also patter songs. Furthermore, it engendered in me a fascination with Gilbert & Sullivan. I was in my element!

The Jesuit chaplain at St Bernadette School, Paul Edwards SJ, was another major influence at this time – not only in supporting my ambition to become a priest but also in encouraging me with public speaking. He was an eccentric character (to put it mildly), flamboyant and affected; and he selected me to enter the Bristol Catenians’ Public Speaking Competition, which I duly won (as reported in the Bristol Evening Post - above).

My two years in the 6th Form also gave me my first opportunity for international travel. Easter 1972 saw me jetting off with my contemporaries to Rome, where we received the papal blessing from Pope Paul VI in St Peter’s Square (right), followed by a further four days based at Massa Lubrensa near Sorrento. This part of the school trip included the Isle of Capri and the ruins of Pompeii in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, and undoubtedly contributed to my love of ancient cultures and foreign climes in later life.

IV

“But Mouse, you are not alone,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes of mice and men

Go often askew,

And leave us nothing but grief and pain,

For promised joy!”

From To a Mouse (modern English version), Robert Burns

After a brief summer holiday stint in the Food Hall of Lewis’s (now Primark) on Bristol’s Haymarket, where I worked on the delicatessen and butchery counters, it was time to fulfil my vocation by commencing my formal studies for the Catholic priesthood. Or so I believed.

My first time away from home, I began to discover my true self, my emotional needs and my sexuality, at St Mary's College, Oscott, in Sutton Coldfield (pictured above and left). Undoubtedly, I encountered many committed and pious young students there, who would go on to lives of dedication within the priesthood. But I also found myself among a group who, like me, felt a sense of liberation socially and sexually. When three of us first-year students decided to drag up to perform ‘Hey Big Spender’ at the Freshers’ Concert, no one batted an eyelid; or, if they did, it didn’t show.

Liturgies, studies and socialising went hand in hand with each other. But I also spent hours alone, usually dressed in my (second hand) cassock, climbing the main tower to meditate, looking across the West Midlands landscape, or walking around the graveyard, contemplating life - and its inevitable end.

By Christmas, I had lost my virginity (to a student-deacon) and had also ventured out into Birmingham and my first gay pub: the Victoria, in the shadow of the Alexandra Theatre. It was here that I met my first love: Chris Cooksey, a drama student from Cradley Heath. The sexual awakening that accompanied my studies at Oscott meant that difficult decisions had to be made. I had been indiscreet and, within six months or so, I found myself summonsed to the Rector’s office to be informed that neither he nor the Diocese of Clifton felt they could continue to support my candidacy for the priesthood: some time away from the seminary would give me longer “to discern my vocation”.

Though this turn of events was initially devastating – made worse by Chris telling me he wanted us to break up – I quickly decided that it provided me with an opportunity. If not a priest, maybe I could be an actor instead! But that profession was decisively vetoed by my parents and, by the time I returned to Bristol in May 1974, I was informed that my mother had already organised a job interview for me. She’d heard on BBC Radio Bristol that they were advertising for a Gram Librarian and had put my name forward.

So began my life as a radio broadcaster – a career which has always been closest to my heart. Although I started on the bottom rung of the ladder (a Gram Librarian was responsible for administering and cataloguing a Local Radio station’s music and for reclaiming audiotape), I soon found myself called upon to provide an occasional voice on air when needed. This progressed to the role of Station or Programme Assistant – a sort of junior producer position, with more presentation responsibilities. My first designated programme was ‘Bedside Manner’, a request show for people in hospital; but broadly, an SA (or PA) could be called on to present (or assist the production of) any genre of programme – from current affairs to light entertainment. So, I worked with Kate Adie on the Arts programme, Eric Hancock on his Classical Music Show and Tony Gibson on Farming. I was appointed producer of ‘Guidelines’, Radio Bristol’s magazine programme for blind and disabled listeners and even the weekly show for the Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities.

In my capacity as producer of ‘Guidelines’, I was approached by a talented and creative colleague, Louis Robinson, who had an idea for a Good Friday documentary. Bristol had been devastated by a wartime blitz in April 1941. As the anniversary approached in 1977, Louis wondered: what would it have been like for those who had not been able to see the carnage, the city’s blind population who could only hear the bombs falling around them and homes, factories, churches and other buildings being destroyed, with the loss of hundreds of civilian lives? The result was a powerful testimony of people’s pain and resilience – narrated by wartime news reader Alvar Liddell (whose commentary we recorded at Broadcasting House in London) – entitled ‘The Sound of War’. It was submitted to the BBC’s London Archives and is a programme of which I am still immensely proud.

I had the good fortune to start my broadcasting life under a wonderful Station Manager, David Waine who, after Bristol, went on to Pebble Mill in Birmingham. David was a quiet man – but inspirational, who always saw potential in people (even green, novice broadcasters like me) and did his best to encourage them. Rather than planning formal post mortems on programmes or interviews, he tended to see you on the stairs and say, ‘Have you got a minute?’ He’d then spend several minutes praising you for a job well done, accentuating the good points about your contribution to the station’s output. Then – ever so subtly – he’d interject ways in which it could possibly have been improved. By the time you left his office, you felt on a high, elated at the affirmation you’d received from the boss, before realising that it had been a serious critique. You could have done better! And it made me even more determined to improve next time. I had tremendous admiration for David Waine, whose style of management I always tried to imitate and who taught me (I hope) how to deal with people and bring out the best in them.

For two years (from a bedsit two minutes away from the studios in Tyndall's Park Road), I rose early to present the 6-7am show, which meant assisting Roger Bennett for the following two hours on the station’s flagship breakfast news programme, ‘Morning West’. This shift also involved being assigned interviews to pre-record during the morning for the following day, so I was given a solid grounding not only in interview technique but also in news gathering.

Although I was rarely assigned the big or ‘heavy’ news stories (and almost never sports stories!), the method was constant: identify what was newsworthy, do the research, contact a spokesperson, record an interview with them (or book them to come into the studio to do it live), then edit it ready for broadcast. It was a good, broad introduction to radio technique, demanding empathy (to get the best out of one’s interviewees) and an analytical approach, but also with a certain degree of theatrical artistry – being able to paint pictures with sound and words. It also created in me a certain discipline, both for time (if you were allotted a three-minute interview, it was non-negotiable) and for priorities: editing required selecting the best bits for broadcast and sacrificing what was less good. Sometimes it hurt to see what ended up on the editing room floor; but the aim was always to present something on air that was informative, educational and entertaining: the best bits of the interview! These disciplines served me well in subsequent years.

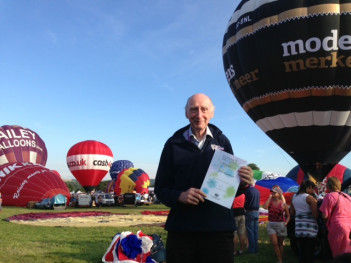

And reporting for Radio Bristol didn't necessarily mean simply holding a conversation. Some of the highlights of this period included some pretty adventurous recordings and live broadcasts: abseiling down the side of the Avon Gorge with the Avon and Somerset Police Rocks Rescue Team, for instance; or trudging through the sewers under the Bristol Maternity Hospital; attempting dry-slope skiing and parasailing on Durdham Downs; and being strapped to a stretcher and lowered down the side of the Unicorn Hotel (now called The Bristol) carpark by paramedics. That was a hair-raising experience - providing live commentary, as the stretcher shuddered and jolted precariousy from the 6th storey as I fought back the urge to utter expletives (it was being broadcast live after all!). There were also glorious outside broadcasts, most notably from the Royal Bath and West Show near Shepton Mallet and the North Somerset Show at Ashton Court, which was also the site of the annual Balloon Fiesta. This was founded in 1978 by local balloon manufacturer and enthusiast, Don Cameron (pictured above) as an event for the local community. Obviously, it merited extensive coverage by the BBC and it's now the biggest balloon event in Europe.

V

“It's one life and there's no return and no deposit;

One life, so it's time to open up your closet.

Life's not worth a damn till you can shout out

I am what I am!”

From La Cage Aux Folles (Jerry Herman)

Above: The Moulin Rouge, Bristol, "a club now run exclusively for the use of Homosexuals", according to a letter from the Worrall Road Residents Association in March 1971. At its peak, it had 1400 members, regularly attracting 500 people on Saturday nights for an entrance fee of 50p. Dave Prowse, the actor who played Darth Vader in Star Wars, worked as a bouncer at the Moulin Rouge in its early days.

This was an interesting time socially, as well. Homosexuality had only been legalised in the UK in 1967, but already by the mid-70s, there were numerous venues for meeting and drinking with like-minded people. On reflection, I can't recall ever feeling a conflict between my sexuality and my faith. If God had made me 'in His image and likeness', He had made me gay. And He loved me as His child, with all my failures and imperfections: being a gay Catholic never felt like it was a contradiction.

The Ship on Lower Park Row (right) was my regular watering-hole, followed by the nearby late night Oasis and 49 Club on Bristol’s famous Christmas Steps, which was run by Wilf (of The Ship) from 1977. And for weekend disco dancing (never my forte!), a trek up Whiteladies Road to Blackboy Hill took you to the Moulin Rouge, Bristol’s premier gay venue build on a former quarry and swimming pool. Interestingly, I recently discovered that it closed in 1976, so I clearly wasted no time in immersing myself in the city’s nightlife once I returned there in 1974!

I still pined for Chris, my first love. And when he saw a photo of him on a shelf in my bedroom, my father informed me – in no uncertain terms – that if he felt that a son of his was a homosexual, it would be equivalent to a daughter of his announcing that she was a prostitute. Fortunately, my parents’ attitude mellowed over the years, so that, by the time I met my one true love and soul-mate in 1992, they treated him almost like an additional son. But, needless to say, during the 1970s, my excursions onto Bristol’s gay scene continued clandestinely.

My interest in the theatre continued and I started working part-time as Box Office Assistant at the Bristol Hippodrome (left). How vividly I recall sneaking in to watch shows at the back of the stalls or hang out with stars of the time (some of them pictured above) – most memorably the lovely John Inman, who played Mother Goose in panto there (1977/78) and Barry Evans, on whom I had a ridiculous crush when he starred with Harry Worth in ‘Cinderella’ (78/79). Visits of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company were times of particular pleasure – not only because I always enjoyed the exceptional standard of their Gilbert and Sullivan productions, but also because I developed a friendship with several members of the cast, in particular Alan Spencer, a chorus-member at the time, who went on to choreograph and direct.

Unfortunately, this infatuation with the theatre resulted in me making a foolish decision in the late ‘70s. The manager of the Empire Theatre in Liverpool (below) was looking for an assistant and, being on the same circuit as the Bristol Hippodrome (Stoll Moss Empires), word had somehow reached him that there was this young, enthusiastic chap called Clapson with potential, working in the box office. I felt flattered to have been headhunted and, as a result, handed in my notice at the BBC and decanted to Liverpool.

It was at this time that I should have learnt a lesson – but I didn’t. Quite simply, I had neither the skills nor the temperament to be management. Some people are natural visionaries, leaders, innovators; others are more suited to the shop floor, grafters, foot soldiers. I was a fish out of water at the Empire; and I was acutely miserable. I was in a relationship at the time with a guy called Melvyn and we had a flat in the really rough area of Kirkby. He managed to get a job as barman in the theatre, while I attempted (unsuccessfully) to revive what had become a lack lustre box office team. Within a year, it was clear – both to me and the management – that this appointment had been a failure. I upped and left, returning to the BBC in Bristol with my tail between my legs.

To my surprise – and delight – I was welcomed back with open arms. But David Waine had been succeeded as Station Manager by Derek Woodcock (who didn’t know me) and there were no full-time vacancies, so I decided to freelance. That was another lesson I learned the hard way: I am not the sort of self-motivating, self-sufficient person who can manage budgets or time-keeping. I needed a structure and an administrative framework that took my income tax (for instance) at source, rather than being expected to become my own personal accountant.

I was, however, responsible for a secret campaign at Radio Bristol in the early 1980s (known as 'Sollydarnosc') that now - after almost 40 years - I am prepared to confess to being behind. It coincided with the Solidarnosc movement in Poland and the appointment of David Solomons (nicknamed 'Solly') as the station's Programme Organiser. David had arrived at the BBC from the Bristol Evening Post where he had been Sports Editor and he had started as the station's News Editor. But when he progressed to Programme Organiser - the person responsible for commissioning and scheduling programmes - it was clear that his vision was limited and two-dimensional. I learnt quickly that the best way to deal with him was to listen to his (usually naive) ideas and to tell him how wonderful they were (he had a very acute ego). Then, slowly in our discussions, I would feed in more practical and interesting elements to embellish his original concept, until it had completely disappeared. Yet he would end up congratulating himself on a brilliant idea!

But 'Sollydarnosc' came about because of his arrogant way of dealing with staff: he would shout and humiliate in a way that left many of them demoralised and, not infrequently, in tears. Mysteriously, overnight, small coloured badges started appearing printed with Sollydarnosc in the style of the Polish labour movement's logo: blue badges were worn discreetly by those who were supporters or friends of those who'd been verbally attacked by Solly (these were the green badge-holders), but the gold emblem was reserved for staff whose shouting match with him had ended with them leaving his office sobbing. The result of this secret campaign was amusing and disrespectful: but it was also a symbol of solidarity and support among BBC Radio Bristol staff that did an incredible amount of morale-building. It generated mutual self-respect among colleagues - especially those who surreptitiously flashed their gold Sollydarnosc badges!

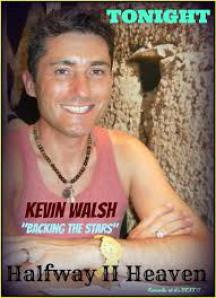

Nevertheless, this period in my professional life was probably one of the most satisfying of all, as I became a full-time freelance producer/presenter at BBC Radio Bristol. I got to interview some of the household names of the day and some of the most memorable are pictured below. People like the outrageous but delightfully warm comedian Jasper Carrott and the raconteur and thoroughly nice guy, Rabbi Lionel Blue; Tony Benn MP was a challenge, but he taught me how a skilled interviewee takes control of an on-air conversation; Warren Mitchell was even ruder and more uncouth in real life than his TV persona Alf Garnett; Roger Moore’s ex-wife, Rosemary Squires, was pure hell to interview (she had her own agenda and no amount of questioning would prompt her to deviate from it); and Barry Humphries insisted on remaining in character when he was interviewed, so it was always Dame Edna Everage or Sir Les Patterson at the microphone, never Humphries himself. Yes, these were indeed interesting times, during which my conversations with the celebrities of the day were broadcast to thousands of homes throughout Radio Bristol's editorial area of Avon, Somerset, South Gloucestershire and West Wiltshire, as well as the City of Bristol itself.

During this period, I also had my own shows – 'Weekend West' on Saturdays (see above), in which I was able to explore in more detail the many and varied events going on in the area, and ‘And So To Ged’. This was an engaging interaction with listeners, three hours on air peppered with anecdotes, music, guests and competitions. The phone-ins were a particular delight and provided many hours during which faithful listeners reminisced about old West Country characters and traditions. The skill of the interviewer, I realised then, was ultimately to ask the questions that made people want to open up to you. History was beginning to come back to haunt me: I was assuming the role of confessor and confidant!

This came to a head during a period when I was a contributor to the station’s religious affairs programme, ‘Genesis’. My own background as a cradle Catholic and former seminarian seemed to qualify me for providing features in the eyes of the producer, Andy Radford, who went on (eventually) to be the Anglican Bishop of Taunton. He was succeeded as religious producer by Diane Shelley. But it was now 1980 and there was a bogeyman on the broadcasting horizon: Radio West, the commercial radio rival to Radio Bristol was due to go on air in October. And Di announced that she intended to join them.

BBC Local Radio felt threatened – almost to the point of paranoia – and nowhere more so than in Bristol under Derek Woodcock. Overnight (literally), the station had a vacancy for a religious affairs producer and I was asked whether I would be prepared to fill it … just for a couple of weeks. That ‘temporary’ assignment lasted for eight years, in which ‘Genesis’ (a half-hour pre-recorded programme comprised totally of talk and hidden away in the schedules) was replaced by ‘Sunday Starts’ – two hours of breakfast-time listening on Sunday morning with music, features and guests with a faith focus.

It was no small challenge to produce and present a weekly peak-time show of this nature. But it was both humbling and immensely satisfying to get messages from many listeners who, for one reason or another, had been alienated from a denominational church, who said that ‘Sunday Starts’ made them feel part of a broader faith community. As one put it, the programme helped her to keep God alive in her heart; and, week after week, I began to realise that religion on radio was a vital ministry and that I, though un-ordained, was a minister in it. I am proud to say too that religious affairs also gained a certain degree of respectability among other members of staff at this time, helped no doubt by events like the visit of Pope John Paul II to Britain in 1982 (above), for which I accompanied a party from a Catholic parish in north Bristol to Cardiff and made a documentary with them about their experience.

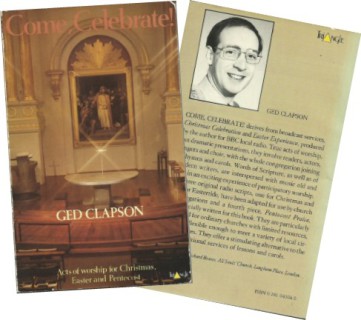

For most of the 1980s, religious broadcasting dominated my life and consumed my creativity. Though untrained and unauthorised by any denomination (but overseen by a Religious Advisory Panel), I was empowered to ‘do God’, reaching tens of thousands of people with the weekly religious affairs programme, by producing the daily Thoughts for the Day and through several major documentaries and outside broadcasts. ‘A Christmas Celebration’ and ‘An Easter Experience’ were major productions, which took us to major churches and cathedrals for a seasonal extravaganza of music and readings for these highlights of the Christian calendar. I was even invited by SPCK to turn some of my original scripts into a book, which resulted in the publication of ‘Come, Celebrate!’ (above) by Triangle Books in 1984.

The following year, I co-led a group of some 250 Radio Bristol listeners on a trip to the Holy Land. When we started advertising it on air, we anticipated a couple of dozen signing up; but we soon had 250 enlisted! So, instead of one coachload who’d be able to stay in one hotel at each site (Tiberias, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv), we had to organise FIVE coaches and FIVE hotels per stop-off. We even chartered our own flight – the first El Al departure from Bristol’s Lulsgate Airport (now Bristol International Airport) – amid unprecedented security.

There were so many highlights on these visits to the Holy Land (in total, I went four times - in 1985 with Radio Bristol and again in 1988 with a private party from a local parish - with each trip needing a reccy several months beforehand). To hear the 'Our Father' in Aramaic (the language Jesus himself spoke), at the site where tradition maintains he said it, was amazing; to view Jerusalem from the very position that he saw it and wept (Dominus Flavit) at the start of his final week was emotional; and to be shown the quarry-side beneath Calvary Chapel in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was a privilege. But it was in Galilee that I experienced my most memorable moment: listening to the Gospel account of the call of the brothers Peter and Andrew, and James and John, and looking out over Lake Tiberias, where modern-day fishermen were tending their nets, brought the biblical account to life with incredible clarity. What was also significant, though, was the way the 1985 trip affected different people in the party. One group of them clearly regarded it as a pilgrimage: they sought out the spiritual dimension in the sites and were often disappointed at the level of commercialism they experienced. But others (I nicknamed them the 'Butlins group') had embarked on the visit principally as a jolly Middle Eastern holiday - yet they found themselves deeply affected by the spirituality of the holy sites that we visited.

In addition to recording throughout the holy sites of Galilee, Jerusalem and Bethlehem (which resulted in six travelogue radio documentaries), we also held an ecumenical service in the Anglican Cathedral (St George’s) in Jerusalem, which I had arranged for the Israeli Broadcasting Authority to record for us for transmission back in the UK. One of our religious leaders - Bishop Peter Firth of Malmesbury - caused a scandal by injecting the Arabic word 'Salaam' into his sermon in the cathedral, alongside the approved Hebrew 'Salom'. It very nearly caused an international incident and it took many months to placate the Israeli authorities and convince them that no disrespect had been intended.

Theatre remained a passion during this period too. I enlisted with the Bristol Musical Comedy Club, securing the role of Sid Pornick in their production of ‘Half A Sixpence’ at the Bristol Hippodrome, and also getting the opportunity to take part in events like the Festival of Remembrance at the Colston Hall – playing Sam Costa in an ITMA (It’s That Man Again) sketch and the Bristol Hippodrome’s 75th anniversary show, which was recorded and broadcast by Radio Bristol. I also joined the Backwell Players, taking on the challenging role of Father James Browne – a disabled priest confined to a wheelchair and living with his two elderly sisters (above). The reviewer in the Bristol Evening Post described it as “the most convincing portrayal of a Catholic priest (he) had seen”!

Backwell also provided me with my first theatrical attempt at comedy, playing Fred Midway – a role originally created by Leonard Rossiter – in David Turner’s ‘Semi-Detached’ (right). It was a new experience to hear an audience responding spontaneously with laughter (hopefully),rather than waiting for their applause at the end of each scene or act.

Derek Woodcock gave me several stimulating radio projects around this time too: firstly, the role of Arts Animateur for all the Local Radio stations in the South West region, which meant visiting galleries and studios, artists and poets, workshops and drama groups, to report on their inspiring work and encourage them – and the radio producers – to use the medium for creative purposes.

I also fronted the region’s evening output. In order to retain a local presence beyond 8pm, a nightly programme was broadcast that pooled some of the highlights from the output of Radios Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, Devon and Cornwall, Solent and the Channel Islands, as well as Radio Bristol/Somerset Sound; so I was introduced to a whole new audience of listeners.

And when the Shepton Mallet brewers Showerings approached Radio Bristol in 1984 with the proposal to invite local musicians to take part in the Babycham Talent Trail – fronted by the BBC Radio 2 DJ, David Hamilton – I was commissioned to produce the series of outside broadcasts across the region.

I even attempted to break into television by auditioning for 'Points West' (the Bristol-based BBC regional news programme) and HTV News – and even going along to the BBC’s Lime Grove studios to audition for 'That’s Life!'. But all of these ventures came to nothing. As one colleague put it (not unkindly, I hasten to add): I had ‘a radio face’!

VI

“And I know, if I'll only be true

To this glorious quest,

That my heart will lie peaceful and calm

When I'm laid to my rest … ”

From ‘The Impossible Dream’, The Man of La Mancha (Leigh & Darion)

Emotionally, I had allowed myself to get involved in what I subsequently realised was an abusive relationship with a guy from Swansea called Philip Hayden (left). How I got into it, or why I suffered it for seven years, or how it resulted in me making one of the most disastrous decisions of my life, heaven only knows! One factor, I recall, was the fact that house prices had risen dramatically in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher, meaning that I had in excess of £30,000 equity in my house in the St George district of Bristol.

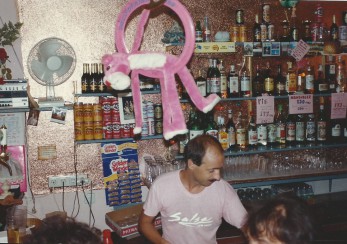

Additionally, I was beginning to feel restless at the BBC. My creativity seemed to have dried up and it felt as though new opportunities were limited; furthermore, BBC Local Radio was going through one of its perennial crises of budget cuts and low staff morale. Maybe I was experiencing a seven-year itch or a mid-life crisis; whatever the reason, Philip and I decided to sell up in the UK, and move all our worldly possessions in a second-hand van to buy a bar in Torremolinos in Spain – the Pink Panther - despite the fact that our relationship had already seriously deteriorated.

The premises looked fine on initial inspection in the autumn of 1988 – ideal for footfall tourists on their way to and from the Costa del Sol beach. But the reality, once we’d moved there at the beginning of the following year, was anything but ‘fine’. It turned out to be in the middle of the town’s drug-dealing district and surrounded by bars with speakers pumping out music at 10-times more megawatts than our simple audio system could generate. The corrupt and bureaucratic Spanish authorities were geared towards getting as much out of foreign investment as they could, with little or no return. The bar didn’t even generate enough income to rent accommodation, so we had to sleep in it (alongside the cockroaches). And, to crown it all, I had agreed to Philip bringing over to Spain with us his new boyfriend, Steve.

Between them (I realised eventually), Philip and Steven saw me as a pushover, a meal ticket, a passport to comforts that they couldn’t afford themselves. Moreover, they had no compunction about using violence and force to get their own way. I can only assume that I was so desperate to find love (which I suppose I did initially with Phil) that I acquiesced, surrendering my life, my money, my security, my dignity – and even my safety – to their brutal regime.

Despite the smile and the suntan (above), those ten months in Spain were probably the nearest thing to hell I could imagine. So much so that by January 1990, I decided I had no alternative but to cut my losses, lock up the bar and take a one-way flight back to the UK. Thankfully, I never saw or heard from Philip or Steven again.

So, for the second time in my life, I returned to the BBC, humbled and emotionally drained. And yet again, I received a warm welcome – this time from Derek Woodcock who was, by now, Head of Broadcasting in Bristol. He immediately assigned me to Radio 2 producer, Stuart Hobday, and the Angela Rippon Show. For the next three months, I acted as their researcher and production assistant. But I still felt restless. I started applying for a broad range of jobs that I felt my skills and experience might be suited to and was eventually invited to London to be interviewed for the post of Head of Communications at the Catholic overseas relief and development agency, CAFOD.

Having returned from Spain penniless and with little more than the clothes on my back, I borrowed a grey suit for the interview from BBC colleague, Joe Kennedy. Joe had moved to the UK from Canada and had worked on the regional TV news programme 'Points West' before transferring to the BBC's internationally-renowned Natural History Unit. We eventually struck up a warm and close friendship that was to last until the present - not least when we discovered we were both gay!

My interviewer at CAFOD was the agency's Head of Overseas Projects, Cathy Corcoran, who was also to become a lifelong friend. Clearly, it was felt that my media experience and Catholic background qualified me to oversee a department that included a press officer, an audio-visual officer and a publications officer because - to my surprise, and forgetting my earlier bad experiences of getting into management – I was offered the job! The suit had obviously made an impression - or so I thought. It turned out afterwards that it looked more silver than grey, a fact that Cathy reminded me of for many years afterwards.

The trip to London for the interview also gave me a brief glimpse of the capital's gay scene, since CAFOD's offices were only one Tube stop from the notorious bars and clubs of Vauxhall. Once my meeting with Cathy (and the Director of CAFOD, Julian Filochowski, who also turned out to be gay) was over, I headed out to explore the infamous Royal Vauxhall Tavern - only to discover that it was closed. What I hadn't appreciated, as a naïve provincial lad of 35, was that many of London's gay venues (with the exception of Sunday lunchtimes) didn't even open until 10pm. The same was also true of the even more notorious Market Tavern, which was to play such a significant part in my life within two years - as indeed were both Cathy and Joe; but that was still a little way off. First, I had to adjust to my new position as Head of Communications at one of the Catholic Church's more prestigious lay organisations in England and Wales - CAFOD.

In addition to the daily responsiblities of generating publicity, liaising with the media and overseeing the production of various publications, I also undertook two overseas trips during my four years at CAFOD: one to Mozambique, where I was able to visit partner agencies and projects supporting refugees and the thousands impoverished by more than a decade of civil war, and the other to Thailand.

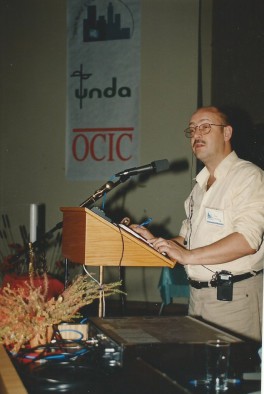

Asia made a deep impression on me, at a number of levels, because my visit there in 1991 was split into three parts. The first part of the trip involved attending the conference of Catholic agencies involved in broadcasting and film, Unda/OCIC (now re-formed as Signis) in Bangkok. This was indeed a fascinating experience that introduced me to people from across the world who were involved in faith-based media and allowed me to hear from such eminent and inspirational speakers as Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini SJ.

Secondly, I joined CAFOD partners working in Bangkok and other regions of Thailand to experience at first hand their work among refugees and the disadvantaged, especially along the Burmese border. It was a whirlwind tour of shanty towns and refugee camps, encountering individuals, families and entire communities living in extreme poverty, victims of severe injustices, threatened with violence and death, yet who remained resilient and whose hospitality knew no bounds. It was indeed a humbling experience and one which strengthened me in my appreciation of CAFOD's vital work overseas; but it was also an emotionally draining one, so I was pleased that I had built in a short holiday at the end of my visit to Thailand, in the idyllic resort in the south of the country, Phuket.

VII

“With one person –

One very special person –

A feeling deep in your soul

Says you were half now you're whole;

No more hunger and thirst …”

From ‘People’, Funny Girl (Jules Styne)

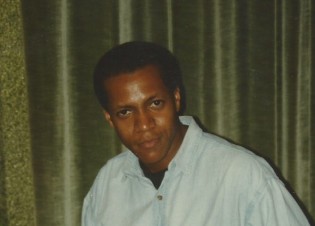

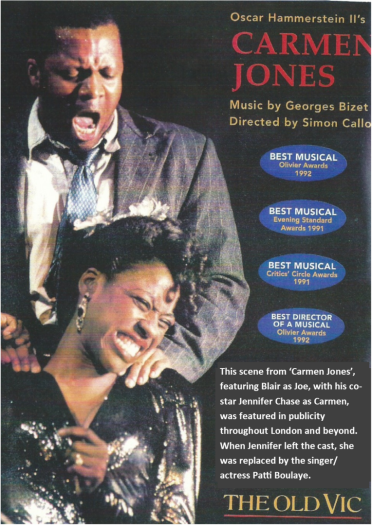

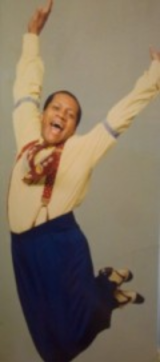

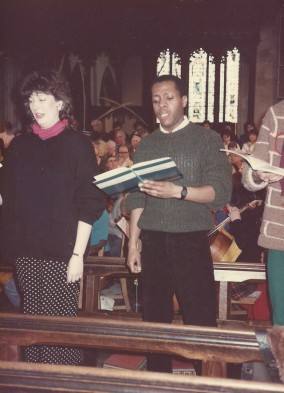

On 4 January 1992, something happened in my life that made my move to London – and all the pain, searching and uncertainty that I had experienced before it – worthwhile. Standing at the bar in the Market Tavern in Vauxhall, I met Blair Patrick Wilson and we struck up a conversation about music. Originally from Philadelphia in the USA, Blair (above) had moved to London to study at the Royal College of Music and had recently landed a role in the chorus of ‘Carmen Jones’ at the Old Vic. This show – an adaptation by Oscar Hammerstein II of Bizet’s opera ‘Carmen’ – had been one of my favourites from as early as I could remember, and it was immediately clear that Blair and I had much in common. I was instantly enamoured by him – his sense of humour, his wicked wit, his handsome features and, perhaps most of all, his generous spirit and selfless love. After so many years of yearning for love, of disastrous relationships, of pain and heartbreak, on that winter's night in south west London, I had at last found true and undying love.

Blair and I struck up a partnership based on mutual love and respect that exceeded all hopes, desires and expectations. He made me feel whole, richer and stronger than I had ever felt in my life. Within a couple of months, the leading role of Joe fell vacant at the Old Vic and director Simon Callow recognised Blair’s talent (and incredible tenor voice) and offered him the part. By the summer of ’92, he moved out of his flat in Thornton Heath and we set up home together in Streatham – a home that was constantly filled with laughter and music and love. I became a regular fixture at the theatre and was able to secure blocks of tickets for friends and colleagues from CAFOD to see ‘Carmen Jones’ and be uplifted by Blair’s talents as a singer and actor. I shall never forget one evening after a performance, when the cast held a party in the Old Vic bar with a live group of musicians. Blair got up to sing and announced to the assembled crowd: ‘This is for my man – Ged!’ He then proceeded to deliver a passionate, bluesy rendition of Gershwin’s ‘Our Love Is Here To Stay’.

After the show closed at the Old Vic, I saw the show at numerous other theatres as Blair toured as Joe throughout the UK, before he went with the company to Japan. An exceptionally versatile performer, once ‘Carmen Jones’ ended, he landed the role of Eat Moe in ‘Five Guys Named Moe’ (right), at which I was also delighted to be able to entertain numerous colleagues and friends. He then went on to join the Royal Shakespeare Company, with whom he sang as Amiens in ‘As You Like It’ at Stratford-upon-Avon, as well as Julien in Molière's 'The Learned Ladies' and Mr Thomas (the butler) in 'Three Hours after Marriage' by John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Arbuthnot. Having started in opera - first with Glyndebourne (Trevor Nunn's 'Porgy and Bess') and Pavilion Opera (London’s premier touring chamber opera) - Blair certainly demonstrated his musical versatility!

In the autumn of 1993, we bought a house (in Valley Road, Streatham) and Blair set about decorating it in his own lavish style: with angels and cherubs, primary colours and opulent furnishings. Within a week of moving in, however, we jetted off to the USA to visit his family in Philadelphia and Mount Vernon and to holiday in Florida. We stopped off at New York, where Blair introduced me to 42nd Street and the Metropolitan Opera House: their production of ‘La Boheme’ was breathtaking.

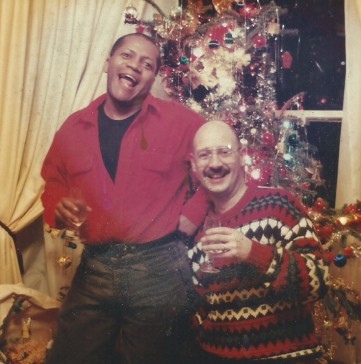

Christmases with Blair were particularly memorable, with a massive, highly-decorated tree and garlands and baubles scattered plentifully around the house, where we welcomed and entertained numerous visitors over the festive season. We are pictured above with my youngest sister, Lucy (Boo) and her daughters, Sally, Emily and Katie. Below, Blair and I enjoy some bubbly in front of the lavishly decorated fireplace in Valley Road.

By 1994, however, my inadequacies as a manager were beginning to show at CAFOD. The department had expanded significantly, incorporating the resources section which distributed books and other materials on behalf of the charity. And, having initially been able to include a practical role in my position as Head of Communications, by writing press releases and getting involved in the day-to-day design of publications, I found myself increasingly pressurised into dealing with strategy and budgets, personnel and other administration matters, which left me feeling frustrated and unfulfilled. By mutual consent, CAFOD’s Director, Julian Filochowski, and I agreed that it would be best if I were to step down and hand over to a more competent manager.

The employment market at that time provided me with the opportunity to explore new ventures – maybe in the commercial sector or at least not faith-related. Or so I thought! Having abandoned my studies for the priesthood 20 years previously, it seemed ironic that I had then gone into religious broadcasting, followed by four years of working for a major Catholic charity. But it was clear that the Holy Spirit had decided that I did have a vocation after all – maybe not as an ordained cleric but certainly as a layman who had a designated role as a communicator within the Church. I was offered the job as Deputy Director of the Catholic Communications Centre (CCC) in London, a role that involved helping the Church to develop its communications and media skills and strategies and providing training for its spokespeople.

We constructed a small radio studio at the CCC in Victoria, which we used for recording interviews and analysing the effective use of the media by trainees – from bishops to charity directors, representatives of religious orders to headteachers in Catholic schools. I also worked ecumenically, leading training days in media skills and public speaking at Church House, the Church of England’s headquarters next to Westminster Abbey. I became a regular contributor to Premier Christian Radio, taking part in the topical discussion programmes, delivering Thoughts for the Day and eventually producing and presenting for them a major 13-part series chronicling Christianity’s 2,000-year history in Britain: ‘A Tapestry of Faith’, which received a Jerusalem Awards commendation in 2003. I was even credited as author (or co-author) of several books in the Catholic Truth Society's series 'The Way, The Truth and the Life', under the auspices of TERE (Teachers Enterprise in Religious Education) and the indomitable Sr Marcellina Cooney CP. And, having first encountered Unda/OCIC at their conference in Thailand in 1990, I became the British Unda representative on their board, eventually being nominated as European President (above). In November 2001, I was one of the delegates who oversaw the amalgamation of the two organisations and their re-emergence as Signis, an event celebrated at the Vatican at an audience with Pope John Paul II (below).

The 1990s also saw my return to Oscott College: not as a naïve virginal student this time, but as a member of their teaching staff! I started providing media training for all the major seminaries in England and Wales – Allen Hall, Wonersh and Ushaw, in addition to St Mary’s, Oscott – with a course that included interpersonal and group communications skills, as well as encouraging them to undertake radio and television interviews when the opportunities arose, as a means of spreading the Gospel. And, though the pennies that I had thrown wistfully into the Trevi Fountain in Rome back in 1972 were probably well-rusted by now, media training with the CCC enabled me to return once more to the Eternal City. For a week every year, I provided a similar course for students at both the Venerable English College in the centre of Rome and the Beda, on the outskirts of the city, where mosquitos enjoyed a regular night-time feast on my English blood and I even got awakened in the middle of the night by the earthquake that devastated Assisi in September 1997 - even though it was 111 miles away!

During this decade, I also found myself rubbing shoulders with and on first name terms with some of the Church hierarchy who had had a significant influence in my life previously. Pictured below are some of them: (from left to right) Patrick Kelly, who had been lecturer in systematic theology at Oscott during my time there, and was now Archbishop of Liverpool; I first met Bishop Crispian Hollis of Portsmouth when he was administrator at Clifton Cathedral in Bristol and a regular contributor to my religious affairs programmes on BBC Radio Bristol; and Vincent Nichols – now Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster – was a close working colleague at the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, where he was its General Secretary at that time.

VIII

“In time, the Rockies may crumble,

Gibraltar may tumble:

They're only made of clay.

But – Our love is here to stay.”

Ira Gershwin

Life at home throughout this decade could only be described as blissful. One of the weekly highlights for Blair and I (when he wasn't touring) was Sunday lunchtime at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, where we were entertained - outrageously - by one of the best drag queens of his day, Adrella (RIP). Our home was constantly filled with music and laughter. Friends were constant guests, among them, my former BBC colleague, Joe Kennedy, and his partner, Dave Smith; and Cathy often joined as with her elderly mother Rita and her sister, Pat.

Despite a few fallow periods (inevitable in the world of the performer, no matter how talented), Blair was a popular singer in a broad range of styles, from opera to blues, film-scores to oratorios – especially Handel’s ‘Messiah’, which was one of his favourites and for which he was in high demand as the tenor soloist, as you can see above.

I accompanied him to numerous concerts and recitals, immensely proud of his achievements and enriched by the love and devotion that he showered upon me. I sometimes wondered: what had I done to deserve the unqualified affection of this beautiful, warm, talented man? Richard Rodgers addressed that in 'The Sound of Music', in the sentimental duet between Maria and Captain von Trapp:

"For here you are, standing there, loving me,

Whether or not you should;

So somewhere in my youth or childhood,

I must have done something good."

Blair and I very rarely disagreed; and, if we did, we had the maturity to agree to disagree, to move away and leave each other space, thereby avoiding disagreements developing into full-blown arguments or rows.

After numerous relationships that had been loveless, miserable and sometimes violent, I had at last found one that was life-enriching and permanent, one free from jealousies and petty bickering, one that would survive because we were totally, utterly and completely in love – and always would be.

Below: a selection of photos featuring Blair that were included in the 'Carmen Jones' programme for the international tour.

While touring with ‘Carmen Jones’ in Japan, Blair had been diagnosed with a kidney condition, which had steadily worsened on his return to the UK. By 1998, he was on dialysis, reliant upon a tube that drew out waste products from his abdomen and filtered his blood twice daily through CAPD (Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis). Although we attempted to continue living life as normally as possible, it was clear that the treatment was restricting his activities – both socially and professionally. His ability to accept singing offers was becoming more limited and – although we managed to transport the necessary bags of fluid for a holiday in the Canary Islands – his mood of dependence on medication and his restricted mobility were beginning to take their toll. At the start of 1999, he was admitted to King’s College Hospital in south London for what we believed to be a standard procedure to improve the level of dialysis. While there, he contracted sepsis and his point of entry for the dialysis became infected with MRSA. He was never to leave King’s alive.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 28 March 1999, I received a call from the hospital. Blair’s condition was critical. He had experienced major organ failure and I needed to get there immediately. Speed limits were ignored as I sped towards Denmark Hill. Blair was already in a coma – still on the ward – and eventually he was transferred to ICU. Supported by my friend and former CAFOD colleague, Cathy Corcoran, and my younger sister, Lucy (who had raced to my side from Gloucestershire), I had to watch his life slowly slip away. Blair Patrick Wilson was declared dead at 0811 on Monday, 29 March 1999. And my world had fallen apart.

We had been together for a mere seven years. We had been looking forward to growing old together. I had been blessed with the most special, the most loving, the most caring soul in the world to be my friend, partner and soulmate. Now I was alone again and inconsolable. I can truthfully say that in all the years that have followed, there hasn’t been a single day when I haven’t thought of Blair and remembered the wonderful times we spent together; haven’t heard his mischievous laughter and soaring operatic voice; haven’t felt the warmth of his embrace. Now, hopefully, my darling, we are reunited. The prophecy of the medallion (pictured above) that you brought me from Japan, which you had inscribed on it ‘BLAIR + GED FOREVER’, has been fulfilled. Though worn and discoloured, I still wear it every day around my neck, encased in the gold ring that I gave you as a token on my undying love.

But life – somehow – had to go on. We gave Blair the best send-off we could think of, with music and tributes, tears and much laughter – at Westminster Cathedral! The Lady Chapel (right) was packed with friends and colleagues from a whole host of opera companies with whom he’d sung – Glyndebourne and Pavilion, the Royal Opera House and, of course, ‘Carmen Jones’. The quality of singing reflected the quality of the singers who assembled there; and the Cathedral’s organist, on realising who he was accompanying, quickly transferred from the small instrument in the chapel to play at full volume on the main organ – not least for Handel's Hallelujah Chorus as we processed from the building at the end of the service. We had received strict instructions from the Cathedral administrator that it was not to be sung but, with typical Blair irreverence, those who’d come to honour this great man sung their hearts out.

My biggest regret about that day is that I didn’t have the sense to request and compose a special service. Blair wasn’t a Catholic, yet I automatically organised a Requiem Mass for him. But at least I was able, several months later, to attend a memorial service organised by his family back home in Philadelphia – in a style much more suited to his heritage and faith. He is pictured here with some of his large American family, including his sister Kim (far left), his late father Roland (seated) and his mother Doris (far right) who died in November 2014.

One thing that I decided immediately after Blair’s death was that he should have a musical legacy: I was determined that his name should never be forgotten. So, I went about establishing the Blair Wilson Award with the Royal College of Music. He undoubtedly had the vocal talent and determination to succeed as a performer when he arrived in the UK from the US; what he hadn’t had was the resources to pursue his studies at the RCM. That had only been achieved through scholarships [he was the first recipient of the Josef Weinberger Scholarship] and financial support from philanthropic agencies and individuals. His legacy, I resolved, would be a similar fund for talented students from overseas, a fund that would grant them access to study to the highest standards and fulfil their musical potential. It turned out that my initial, lofty objectives were far too ambitious: the donations that I collected around the time of his death and funeral languished in a bank account.

But eventually, I was able to realise the ambition and set up the Blair Wilson Award with the RCM, welcoming Oscar Castellino (left) from India as its first recipient. It is my intention to expand this fund substantially on my death, so that Blair and I have a joint legacy through musical excellence. Many years from now, hopefully, people will still remember Blair Patrick Wilson; and - since I have no heirs to continue the line - the name ‘Clapson’ will be perpetuated through an award with the RCM that will encourage them to fulfil their dreams and succeed in life – whether they have the personal financial resources or not.

IX

“And numbed with grief, I couldn’t speak.

I shut myself away, week after week.

The weeks turned into years

And life grew ever bleak –

Without (him).”

From Goodnight Mr Tom (Michelle Magorian)

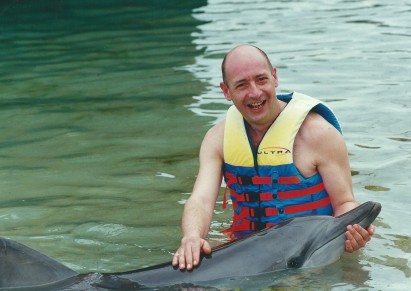

Smiling through grief: Swimmng with dolphins in Australia helped me to cope after Blair's death in 1999.

Smiling through grief: Swimmng with dolphins in Australia helped me to cope after Blair's death in 1999.

The months following Blair’s death in 1999 are little more than a blur. My father died shortly before Christmas and we had to wait until the New Year (and a new millennium) before we could hold his funeral service. I know that I bought a ticket and flew to Australia (right) some time in 1999, where I stayed with my former BBC colleague, Chris Kearns, with whom I'd worked on the Angela Rippon Show; I know I started becoming more promiscuous and drinking more; and I know that an old friend whom Blair and I had first met on holiday in Gran Canarias, Stephen Saunders, moved in to help support me through this first difficult period. I even returned to work at the Catholic Communications Centre – eventually. But I remember little detail of the rest of the millennium.

In the summer of 2000, however, I met Frank Temple, who has been my friend and companion ever since. We met at The Stag in Victoria (left) and, after an initial, brief ‘fling’ (which gave us enough time to ascertain that we were incompatible as lovers), we struck up a friendship. I had become a regular at The Stag and had taken up karaoke. Somehow, after Blair’s death, I found the voice – and the nerve – to perform on stage as myself, not hidden behind a character in a script; I found my own musical style (big band and show tunes); and karaoke became (and remained) close to an obsession. I also started working at the pub, and found engaging with the punters most satisfying.

After a few months, Frank moved in and has remained a pivotal point of stability and reason in my life ever since. We complement each other – although we constantly confuse people when we explain that we are ‘not a couple’. The Golden Girls is about the best comparison I can think of to explain our odd relationship. But through the years, Frank has been tremendously supportive to me – as I hope I have been to him – through very difficult times.

One of these times came in 2002, when the Catholic Bishops’ Conference – having carried out an audit of their communications resources in England and Wales and concluded that the most effective operation by far was the training and support provided by the Catholic Communications Centre – decided to close down the CCC! So, faced with redundancy, I decided to attempt to go it alone independently, offering my skills as communications consultant and media trainer to church organisations and charities, as well as taking on the odd broadcasting assignment, such as the Night-time Pause for Thought on BBC Radio 2 (my voice was my passport, thankfully; it certainly wasn’t my profound intellect or theological knowledge!).

I built up a reasonable portfolio of clients requiring media training – from the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award to Investors in People, CAFOD to the Church of England, for whom I became their regular public speaking trainer. The transferrable skills required for broadcasting, I found, applied just as much to addressing an audience; and it felt enormously gratifying when a previously dull, nervous speaker gained in confidence and started to discover how recounting stories or using imagery (painting pictures with words – as was so vital on radio) rather than simply cold facts or statistics could engage with people in a creative way.

Training and consultancy at the Catholic Communications Centre also brought me into contact with various religious orders, among them the Jesuits. Having worked behind the scenes on the drafting of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference’s policy on child protection, I was reasonably well placed to advise the Jesuits on media relations when they faced allegations of abuse by members of the order (Operation Whiting 1999). Among those to whom I offered advice and media training was the Jesuit Provincial at the time, David Smolira SJ (above). And when he decided in 2002 that the Jesuits required a Communications Officer to develop their public profile – particularly in the media – he asked whether I would be interested in the position.

A rare and significant family photo. Rare because it brought together the five siblings (and Boo's three daughters) - on 27 March 1999, to celebrate mum and dad's Diamond Wedding anniversary. Significant because, though we didn't know it at the time, Blai

A rare and significant family photo. Rare because it brought together the five siblings (and Boo's three daughters) - on 27 March 1999, to celebrate mum and dad's Diamond Wedding anniversary. Significant because, though we didn't know it at the time, Blai

Reluctant to abandon the pool of clients I had amassed both as Deputy Director at the Catholic Communications Centre and subsequently as a freelance trainer and consultant, I accepted on a part-time basis. Additionally, my mother was becoming increasingly frail by this time: she eventually passed away in May 2003 and we celebrated her life with a Requiem Mass at St Teresa’s Church in Filton, at which Father Barnabas Page – whose family we had known since our days in Ravenswood Road and with whom I studied as a seminarian at Oscott College back in the early 1970s – officiated.

Within a year or so, it soon became evident that my role with the Jesuits demanded full-time commitment. So, I took on the task not only of helping to promote them in the press, on radio and television, but also working on their publications, especially the editing of their magazine Jesuits and Friends. The role of Communications Officer involved travelling the length and breadth of Britain, visiting the communities, parishes, schools and other centres where the Jesuits were active, with a view both to generating stories about the work that they were doing and also encouraging personnel at these operations to make publicity a priority. The British Province at that time included South Africa, so my induction even included a visit to the Southern Hemisphere to see at first hand ways in which the Jesuits were supporting the Catholic community – and the broader population of South Africa – and attempts to develop ways of publicising them.